… And they have diabetes!

Dr. Jeff Spindel

In this blog post we’ll be going over how to manage diabetes mellitus type II in the inpatient setting when diabetes is not the reason for admission.

The goals for management of diabetes as an inpatient are to prevent hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic events, minimize disruption of the metabolic state and treatment of the primary illness, and facilitate a smooth transition to outpatient care.

Complicating these goals are the stresses of the acute illness, which often leads to an adrenergic state and hyperglycemia. Conversely, anorexia or an NPO order, either due to illness or in anticipation of a procedure, can cause hypoglycemia, as can a stricter inpatient diet.

Avoid hypoglycemia (BG <70 mg/dL): Since causes of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia are not predictable, inpatient glucose targets are more lenient than outpatient targets. A landmark RTC compared a BG target of 80-110 versus 180-215 mg/dL in critically ill patients and found an absolute risk reduction of 3.4% for mortality at 12 months due to associated reductions in multi-organ failure, bacteremia, renal failure requiring dialysis, and blood transfusions, establishing the need for intensive blood glucose control.¹ However, a follow up RTC, amusingly titled the “NICE-SUGAR Study,” further narrowed the target. In this study of critically ill patients, a target BG of <180 was compared to a target of 80-108 mg/dL. The less stringent target blood sugar resulted in an absolute risk reduction for mortality of 2.6%. While there was no difference in length of hospitalization, ICU stay, or mechanical ventilation, severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) occurred in 6.8% of the intensive therapy group compared to only 0.5% of the lenient group and was likely the cause of adverse outcomes.² Various follow up studies and meta-analyses have been performed, determining that, for each day of hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), length of stay increased by 2.5 days. For every 10 mg/dL decrease in lowest BG, risk of death increased 3x.3 Furthermore, hypoglycemia increased risk of death up to 1 year from discharge.³ While not strictly validated in non-critically ill patients, current guidelines apply these studies to all hospitalized patients.

Therefore, target BG in most admitted patients with DM is 140-180 mg/dL.⁴ [American Diabetes Association]

2. Avoid metabolic derangements: These include acid/base disorders, kidney injuries, and electrolyte disturbances. Electrolyte disturbances can occur with hypo- or hyperglycemia. And since many of the antihyperglycemics used in the outpatient setting can complicate or worsen metabolic derangements, the preferred agent for inpatient management of diabetes is insulin. There are a few exceptions. Common adverse effects and drawbacks of non-insulin therapies are detailed below.

a. Metformin – risk of lactic acidosis

b. DPP4 inhibitors – mainly effect postprandial glucose. In patients that are not eating, little benefit

c. Sulfonylureas and Meglitinides – risk of hypoglycemia

d. GLP-1 agonists – mainly effect postprandial glucose

e. SGLT2 inhibitors – risk of dehydration, UTI, euglycemia ketoacidosis. However, they are increasingly being used inpatient for acute decompensated heart failure.⁵

f. Thiazolidinediones – fluid retention.

g. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors – antihyperglycemic only when eating, can cause electrolyte abnormalities and diarrhea.

Insulin is preferred in the management of inpatient diabetes, even in insulin naïve patients.

3. Facilitate a smooth transition to outpatient blood sugar control: Good inpatient control will facilitate good outpatient control. If possible, resume oral meds 1-2 days before hospital discharge. If outpatient medications are changed, perform a thorough medication reconciliation with documentation and schedule follow up in 1-2 weeks with either the patient’s primary care provider or endocrinologist.⁴

Various regimens exist based on if a patient already uses insulin, body mass, and needs. The most common and the most studied regimens are basal-bolus and sliding scale insulin. Basal-bolus regimens consist of long acting and short acting mealtime insulin and have the benefit of a proactive approach. Sliding scale insulin (SSI) is reactive, with dosing based on blood sugar at the time of administration. A large meta-analysis compared basal-bolus insulin versus sliding scale insulin (SSI) alone in non-critically ill patients and found no difference in mortality.6 However, sliding scale insulin (SSI) for >24 hours is discouraged by the American Diabetes Association on the most recent recommendations.⁴

So how do you transition a patient to an inpatient insulin regimen? If they are already well controlled on a home insulin regimen, use that as a starting point. One preferred method is to decrease the home dosage by 33-50% and add a sliding scale as supplementation. The reasoning for this is that the inpatient blood glucose target is higher than the outpatient target because of the acute illness, fasting episodes, and more tightly controlled diet inpatient. The addition of a sliding scale will help limit hyperglycemia using fast acting insulin.

A 60 year old male with type II diabetes is admitted for a COPD exacerbation. He takes 30 units of insulin glargine at night and 10 units of insulin aspart three times per day with meals. His most recent A1c was 7.1%.

Judging by his A1c, he is relatively well controlled at home. After confirming that he takes the insulin as prescribed, a reasonable regimen would be a 33% reduction in dosage and a sliding scale. Therefore, his inpatient regimen is 20 units of glargine at night and 6 units aspart TID AC and a sliding scale.

For patients on a home insulin regimen, decrease dosage by 33-50% and add a sliding scale protocol.

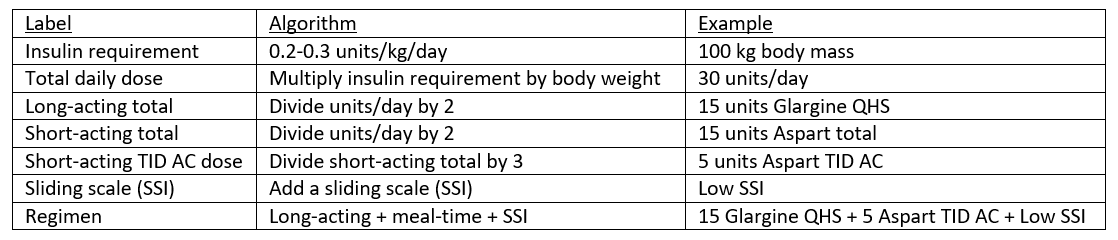

What if a patient does not take insulin at home? Weight based dosing is appropriate in these circumstances. Generally, non-obese insulin naïve patients require 0.2-0.3 units of insulin per kilogram body weight per day. Obese patients may require more insulin, generally 0.3-0.5 units/kg/day.

A 65 year old female with type II diabetes is admitted for heart failure exacerbation. Her outpatient antihyperglycemic regimen is currently metformin 1000 mg BID, glyburide 5 mg daily, and empagliflozin 10 mg daily. Her weight is 135 kg, BMI is 48 kg/m2 and her most recent A1c was 7.8%.

Firstly, her home regimen should be held. Some experts continue SGLT-2 inhibitors in the inpatient setting treatment of cardiac comorbidities,⁵,⁷ but that discussion is beyond the scope of this post. Since she is not on insulin and is obese, a higher weight-based dosing is necessary. A reasonable starting point in this case is 0.3/kg/day. Based on the patient’s weight, her total daily insulin requirement is 40.5 units [135 kg * 0.3 u/kg/day]. Dividing this between long and short acting, her initial regimen will be 20 units of long acting insulin daily and 7 units of short acting TID AC. In addition, start a sliding scale.

In insulin naïve patients, use weight-based dosing and split the total daily requirement between long and short acting insulin. Also add a sliding scale.

Now, how do you make adjustments to the regimen? A general rule is that if a patient is persistently above the target BG of 140-180, dosing should be increased on both long and short acting. A simple method is that if the BG is persistently above 200 mg/dL, increase the total regimen by 20%. If persistently above 300, increase by 30%. If persistently above 400, it’s time for a drip. Don’t forget to account for the sliding scale received.

On day 3 of hospitalization, after a complete course of the structured insulin regimen, the 65 year old female admitted for HF has had persistently elevated blood glucose, ranging from 202-297. She has received 20 units glargine, 7 units of AC aspart 3 times, and has received sliding scale insulin 4 times, totaling 12 units.

First, add everything including the sliding scale. [20+7*3+12 = 53 units] Now, increase the total by 20% since her BG was persistently above 200. [53*1.2= 63.6 units] As before, divide this among long and short acting. The new regimen is 30 units glargine, 11 units aspart TID AC, and the continuation of sliding scale. Corrections like this should be performed daily.

Reformulate insulin regimens daily and increase total daily insulin based on the level of hyperglycemia.

What if the patient has hypoglycemic episodes? This is a big red flag. First, make sure they are eating. If they are not, make sure they have not been receiving mealtime insulin. To be safe, consider using sliding scale insulin alone for 24 hours and then calculating the total daily dosing the following day.

If hypoglycemic episodes occur, look for causes, reduce insulin dosing, and consider a transition to only sliding scale insulin for 24 hours.

Hopefully this blog post will prove helpful. One note I would like to make is that the above insulin dosing only applies to patients who are eating by mouth. For patients who are NPO or are receiving tube feeds, dosing and preferred insulins are different. These will be covered in future blog posts.

Summary:

Target BG in most admitted patients with DM is 140-180 mg/dL.⁴ [American Diabetes Association]

Insulin is preferred in the management of inpatient diabetes, even in insulin naïve patients.

For patients on a home insulin regimen, decrease dosage by 33-50% and add a sliding scale protocol.

In insulin naïve patients, use weight-based dosing and split the total daily requirement between long and short acting insulin. Also add a sliding scale.

Reformulate insulin regimens daily and increase total daily insulin based on the level of hyperglycemia.

If hypoglycemic episodes occur, look for causes, reduce insulin dosing, and consider a transition to only sliding scale insulin for 24 hours.

Jeff Spindel, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Medicine | Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine

Jeffrey Spindel is currently a resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Louisville. His current research and academic interests include the effects of blood glucose control on the incidence of major adverse cardiac events and utilization of low cost coronary artery calcium scoring for risk stratification in asymptomatic patients.

References:

van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1359-1367. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011300

NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, Finfer S, Chittock DR, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283-1297. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810625

Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, Scanlon JV, Greenwood B, Pendergrass ML. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1153-1157. doi:10.2337/dc08-2127

American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S211-S220. doi:10.2337/dc21-S015

Griffin M, Riello R, Rao VS, et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors as diuretic adjuvants in acute decompensated heart failure: a case series. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(4):1966-1971. doi:10.1002/ehf2.12759

Colunga‐Lozano LE, Torres FJG, Delgado‐Figueroa N, et al. Sliding scale insulin for non‐critically ill hospitalised adults with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;(11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011296.pub2

Koufakis T, Mustafa OG, Ajjan RA, et al. The use of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in the inpatient setting: Is the risk worth taking? Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2020;45(5):883-891. doi:10.1111/jcpt.13107