Baby It’s Cold Outside: Hypothermia Management

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

Case

A 20-year-old male presents after falling through the ice on a partially frozen lake while ice skating. He was submerged from the chest down for several minutes before he was able to be rescued. He arrives via emergency medical services wrapped in blankets, but still wearing wet clothing. Core temperature is below 30oC. Your medical student asks how they can assist in warming the patient.

Hypothermia

Body temperature reflects the balance between heat production and loss. Accidental hypothermia is the unintentional drop in core body temperature to less than 35oC and develops when the body is not able to generate enough heat to keep up with losses.¹

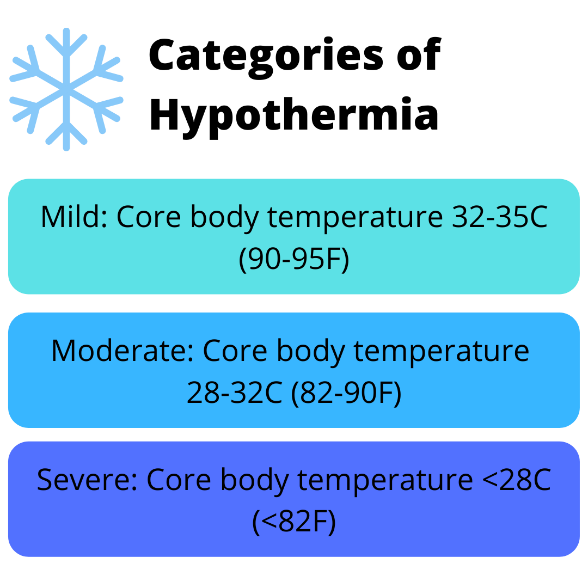

Hypothermia can be separated into three categories:

Mild: core body temperature 32-35oC (90-95oF)

Moderate: core body temperature 28-32oC (82-90oF)

Severe: core body temperature <28oC (<82oF)

The most common mechanisms underlying hypothermia are heat loss through convection (transfer of heat to air or water currents) and conduction (transfer of heat to a colder object). It is often seen in environments with a harsh winter, however, can also be seen in warmer climates and in the summer.

Hypothermia may be accompanied by trauma, drowning, or diseases that affect thermoregulation such as cerebrovascular diseases.¹ Young children are predisposed to hypothermia due to larger surface area to body mass ratio compared to adults, lack of subcutaneous tissue, and poorly developed thermoregulatory systems. Infants are at even greater risk as they are unable to shiver and depend on others to move them from a cold environment.²

The Swiss System

When temperature is difficult to measure, for example when an initial rescue is taking place, the Swiss System can be used to stage hypothermia:¹

Mild (Grade I or HTI): Normal mental status with shivering, estimated core temperature 32-35oC (90-95oF)

Moderate (Grade II or HT II): Altered mental status without shivering, estimated core temperature 28-32oC (82-90oF)

Grave (Grade III or HT III): Unconscious with vital signs, estimated core temperature 24-28oC (75-82oF)

Deep (Grade IV or HT IV): Apparent death due to absence of vital signs, core temperature 12.7-24oC (56.7-75oF)

Irreversible (Grade V or HT V): Death due to irreversible hypothermia, resuscitation not possible, core temperature <9-13.7oC (<48.2-56.7oF)

Rewarming

Rewarming is key to treatment of hypothermia and should begin as soon as possible.

Pre-Hospital Setting

In the pre-hospital setting, the goal is to prevent further heat loss until the patient can be transported to the hospital setting where more resources are available. Patients should be wrapped in an insulating material such as insulating blankets, plastic sheeting, trash bags, or any other material that is able to create a sealed layer. When wrapping the patient, keep in mind that the most heat loss occurs as the result of direct contact with the ground or stretcher and exposure of the head and neck to the environment. When wrapping the head and neck, remember the patient’s face should remain exposed to allow breathing.¹

Patients who are wet may benefit from remaining in the wet clothing in some situations, as it requires less movement and less exposure to environmental cold.¹ Additionally, if available reflective blankets, warm and humidified oxygen, or heat packs applied to the axilla, chest, and back can be used.

Hospital Setting

Once in the hospital setting, more aggressive rewarming can begin. Initial strategy is based on the degree of hypothermia.³

Mild hypothermia: passive external rewarming

Moderate hypothermia: active external rewarming

Severe hypothermia: active internal rewarming and possibly extracorporeal rewarming

Passive External Rewarming

Wet clothing is removed, and patient is covered with blankets or other types of insulation. Room temperature should be maintained at 28oC (82oF).³

Core temperature should be increased by 0.5-2oC per hour. Active rewarming is often added to passive rewarming for patient comfort and to decrease cardiovascular energy, as passive rewarming works through increased metabolic rate and shivering. Active rewarming should be implemented if rate of rewarming falls below 0.5oC per hour, dysrhythmias are present, older adults who may not have the physiologic reserve to support passive rewarming, suspected sepsis, or failure to respond to passive rewarming.³

Active External Rewarming

A combination of warm blankets, heating pads, radiant heat, warm baths, or forced warm air are applied directly to the patient’s skin. Rewarming of the trunk should be done before the extremities to prevent afterdrop.³

Afterdrop is the additional drop in core body temperature once rewarming has started and has the highest incidence in patients with moderate to severe hypothermia. When rewarming begins, peripheral veins dilate and the cold blood with acidemia that has accumulated in the extremities returns to the heart. This can trigger ventricular fibrillation. To help avoid afterdrop, exclusive rewarming of the extremities should be avoided, and instead rewarming should focus on the torso.¹

Core body temperature generally increases at a rate of 2oC per hour using active rewarming.³

Active Internal Rewarming

Endovascular rewarming is the method of choice. If this is not available, alternative methods include peritoneal and pleural irrigation.³

In endovascular rewarming, a closed catheter tip is inserted into the femoral vein. The catheter circulates temperature-controlled water, warming blood as it flows past a tip. A thermostat is connected to an esophageal temperature probe, and the patient is rewarmed until temperature reaches 30oC (86oF).³

Peritoneal irrigation is performed by infusing 10-20 mL/kg of isotonic saline warmed to 42oC (107.6oF) into the peritoneal cavity. The fluid is left in the peritoneal cavity for 20 minutes and then removed. Typically, two catheters are placed, one for instillation and one for drainage.³

Pleural irrigation is performed by infusing 200-300 mL of isotonic saline warmed to 40-42oC (104-107.6oF). Two thoracostomy tubes are placed in one or both hemithoraces, one tube is placed high and anterior and the other is placed low and posterior. Warm fluids are inserted through the anterior tube and drain posteriorly.³

Heated humidified oxygen and heated IV or IO fluids are used to prevent further cooling. In the past these were sometimes considered active internal rewarming, however they have minimal effects on raising temperature and should be used in combination with other methods.⁴

Extracorporeal Blood Rewarming

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be needed in patients with hemodynamic instability, cardiac arrest, severe rhabdomyolysis with hyperkalemia, completely frozen extremities, or who do not rewarm with less invasive active internal rewarming techniques. Hemodialysis can also be used for rearming.³

Resuscitation

Patients with respiratory distress or who cannot protect their airway should be intubated. Endotracheal intubation in a hypothermic patient can cause ventricular fibrillation, however if the patient is unable to protect their airway, the benefits outweigh the risks. Standard medications can be used to perform rapid sequence intubation. The use of a supraglottic device should be considered in patients with trismus caused by the cold, as this is usually resistant to neuromuscular bock.¹

Peripheral pulses may be difficult to palpate due to vasoconstriction. Central pulses should be checked for up to a full minute, using Doppler if available.³

As there is no convincing data for setting a lower limit for successful resuscitation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be attempted in all patients, regardless of core body temperature.¹

Arrythmias such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation usually do not respond to defibrillation until core body temperature reaches 30oC (86oF). In this situation, three cycles of epinephrine/defibrillation should be attempted. If unsuccessful CPR should be continued and defibrillation reattempted with every 1-2oC increase in temperature.1 Once the core body temperature has reached 30oC guidelines for normothermic patients should be followed.³

Fluid Resuscitation

Patients often become disproportionally hypotensive during rewarming due to dehydration and fluid shifts. Blood pressure should be supported with warmed isotonic fluids [40-42 oC (104-107 oF)]. Use of warmed fluids is critical as infusion with room temperature fluids may worsen hypothermia. Intravenous access may be difficult, so an intraosseous or central line may be needed. When placing a central line, femoral access is preferred to avoid precipitating an arrythmia.³

Norepinephrine is the medication of choice to maintain blood pressure in fluid refractory patients.³

Duration of Resuscitation

Given hypothermia is neuroprotective, resuscitative efforts should be continued for a prolonged period of time. Biochemical markers can help decision making around resuscitation cessation.³

Extreme hyperkalemia reflects cell lysis and may predict futile resuscitation. There are no reported cases of survival when the patient’s serum potassium exceeds 12 mEq/L (mml/L)

Poor prognosis is seen with:

Fibrinogen concentrations below 50 mg/dL (1.5 mmol/L)

Ammonia concentrations above 420 mcg/dL (250 mmol/L)

Elevated lactate

Elevated serum sodium

Elevated creatinine

Patients with persistent asystole after core body temperature is higher than 32oC (89.6oF) likely have irreversible cardiac arrest, and termination of CPR should be considered.⁵

Additional Evaluation and Workup

A total body survey should be done in all hypothermic patients to assess for signs of trauma and evaluate for local cold-induced injuries.

Laboratory studies should be obtained to identify potential complications and comorbidities.²

Arterial blood gas will show evidence of decreased tissue perfusion and metabolic acidosis

Serum electrolytes should be monitored during the rewarming process

Serum glucose is elevated due to the catecholamine effect and insulin inactivity below 30oC (86oF)

Clotting studies may demonstrate cold induced thrombocytopenia and prolonged clotting times. Persistent changes following rewarming suggest development of disseminated intravascular coagulation

Amylase and lipase may be elevated due to pancreatitis and is associated with poor outcome

Cultures of body fluids are indicated in infants as sepsis is a common cause of hypothermia in this population

Chest radiograph is indicated in all cases of significant hypothermia. Aspiration is common and pulmonary edema may develop during rewarming

In settings of trauma cervical spine imaging as well as head computer tomography (CT) are indicated. Head CT should also be considered where altered mental status does not improve with rewarming

Electrocardiogram is indicated for all patients with a core temperature <32oC (89.6oF) to look for dysthymias or evidence of myocardial ischemia

The J-wave (Osborn wave) is pathognomonic for hypothermia, but has no prognostic or predictive value

The J-wave is a notching at the junction of the QRS complex and ST segment and is typically seen when temperature falls below <32oC (89.6oF)

Benign atrial dysrhythmias are common at body temperature <32oC (89.6oF)

Ventricular ectopy with risk of ventricular fibrillation occurs at <30oC (86oF)

Asystole typically occurs at <19oC (66.2oF)

Disposition

Most patients with hypothermia require hospitalization. Patients with mild hypothermia may be rewarmed and discharged to a safe environment if there is no evidence of underlying disease.²

Back to the Case

You explain to the medical student that our patient that fell through the ice has a core body temperature of 30oC, which we could categorize as moderate hypothermia (core body temperature 28-32oC). The patient will benefit from using both active and passive externally rewarming initially.

You remove his wet clothing and apply a forced air warming system and warm blankets. Physical examination does not show any evidence of trauma and the patient is has a normal neurological examination.

While continuing to monitor the core body temperature, an electrocardiogram and labs are obtained. Electrocardiogram shows the pathognomonic J-wave, but no evidence of arrythmia. Labs are overall reassuring. After several hours in the emergency department the patient demonstrates continued improvement in core body temperature. Given how low his temperature was on arrival, patient was admitted for observation and continued management.

Bottom Line

Hypothermia is the unintentional drop in core body temperature to less than 35oC and can be separated into three categories: mild (32-35oC), moderate (28-32oC), and severe (<28oC). Both active and passive rewarming methods are typically used, and patients with higher categories of hypothermia often require more invasive rewarming. The torso should be rewarmed before the extremities to prevent afterdrop. If CPR is indicated, it should be attempted in all patients regardless of body temperature. As hypothermia is neuroprotective, resuscitative efforts should be continued for a prolonged period of time. Ventricular arrythmias may be initially unresponsive to conventional therapy until the patient is rewarmed to 30oC (86oF).

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References:

Avellanas Chavala ML, Ayala Gallardo M, Soteras Martínez Í, Subirats Bayego E. Management of accidental hypothermia: A narrative review. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2019;43(9):556-568.

Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Just the Facts, 2e.: McGraw Hill; 2013.

Zafren K, Mechem C. Accidental hypothermia in adults. 2021; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/accidental-hypothermia-in-adults.

Corneli HM. Accidental hypothermia. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(5):475-480; quiz 481-472.

Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1930-1938.