Frostbite

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

Case

A 12-year-old boy presents to the emergency department with pain, redness, and blisters to multiple toes. The patient had been sledding earlier in the day when he fell into a pond, getting his legs and feet wet. He continued to sled after the fall but decided to go home when he could no longer feel his toes. He walked home in the snow, removing his boots and socks when he got home. He reports that initially he was unable to feel is toes, but they became painful while watching cartoons. You are concerned for frostbite and pause to think about the next steps in management.

Introduction

Frostbite occurs when tissues are exposed to temperatures below their freezing point, typically below 0oC (32oF).¹,² Any portion of exposed skin can experience frostbite. The most susceptible areas are earlobes, noses, hands, and feet.¹

It is seen most commonly in mountaineers and other cold weather enthusiasts, soldiers, the homeless, and those who work in cold environments.³

Tissue destruction is caused by formation of ice crystals, hypoxia secondary to cold-induced local vasoconstriction, release of inflammatory mediators, and thrombus formation. Repeated thawing and freezing of the affected area worsens the initial damage.¹

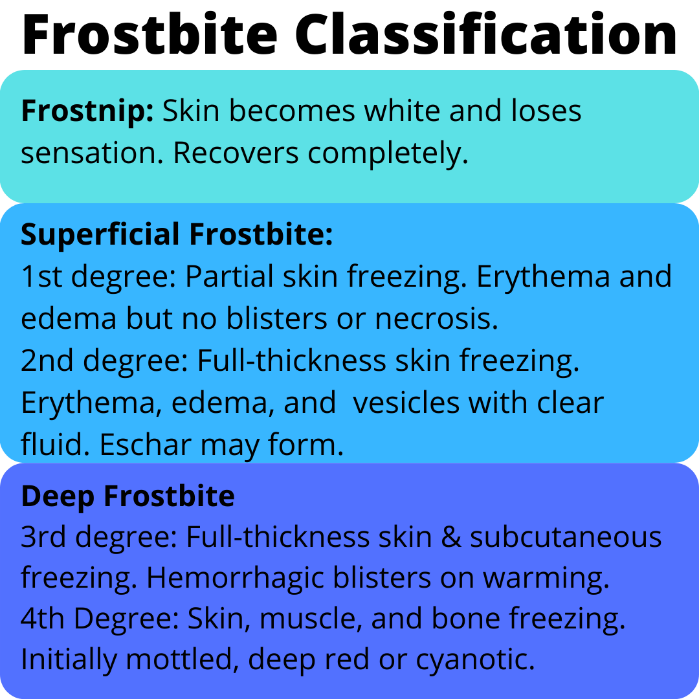

Classification

Frostbite is classified according to the clinical presentation and depth of injury: ¹,³

Frostnip: cold induced local paresthesias that resolve with rewarming. No permanent tissue damage.

First-degree frostbite: limited to the superficial epidermis. Central area of pallor and anesthesia surrounded by edema. Resolves without sequelae.

Second-degree frostbite: deeper epidural involvement with large blisters with clear fluid surrounded by edema and erythema. Blisters may form an eschar that later sloughs off revealing healthy granulation tissue. There is no tissue loss.

Third-degree frostbite: full thickness skin injury associated with hemorrhagic blisters on rewarming. The skin forms a black eschar in one to several weeks.

Fourth-degree frostbite: extends to the muscle and bone, involves complete tissue necrosis. Mummification occurs in 4-10 days.

As edema and bullae do not appear until rewarming, this classification system can underestimate the extent of frostbite on initial presentation. A clinical predication tool has been developed for frostbite injury of the hands and feet based on the level of skin lesions noted after rewarming, and may be more useful:³

Grade 1 frostbite: no cyanosis on the extremity. Predicts no amputation and no sequelae.

Grade 2 frostbite: cyanosis isolated to the distal phalanx. Predicts only soft tissue amputation and fingernail or toenail sequelae.

Grade 3 frostbite: cyanosis of the intermediate and proximal phalanges. Predicts bone amputation of the digit and functional sequelae.

Grade 4 frostbite: Cyanosis over the carpal or tarsal bones. Predicts bone amputation of the limb with functional sequelae.

Other Cold Injuries

Chilblains: local inflammatory lesion that can result from acute or repetitive exposure to damp cold above the freezing point. Lesions are edematous, red or purple in color, and may be painful or pruritic. Symptoms general resolve within two to three weeks and permanent damage is uncommon.

Immersion foot (trench foot): injury to the sympathetic nerves and vasculature of the feet due to prolonged exposure to a combination of dampness and cold. Feet are often edematous and can be numb or extremely painful period in severe cases can be covered with hemorrhagic bullae. While often associated with historical warfare, this can still be seen today, especially among the homeless.

Treatment

Prehospital Care

Patient should be moved to a warm environment as soon as possible and any wet clothing should be removed. If frostbite occurs on the feet, walking should be avoided if possible as this can increase tissue damage. If walking is necessary for evacuation, warming should be delayed until after walking.³ Additionally, removal of boots should be delayed until after walking, as once the boots are removed edema my prevent them from being put back on.⁴

Frostbitten tissue should not be rewarmed if there is a possibility of refreezing before reaching definitive care, as this results in worse tissue damage. If prehospital warming is attempted, affected area can be placed in warm water or warmed using body heat, for example, placing frostbitten fingers in the axilla for 10 minutes. Rubbing the area should be avoided as this can cause further damage. Use of stoves or fires should also be avoided, as frostbitten tissue maybe insensate and patient may sustain burns.³

Hospital Management

Rapid rewarming, wound care, and efforts to enhance tissue viability are the mainstay of initial treatment. However, management of more serious conditions, such as severe hypothermia, take priority over treatment of frostbite.

Rewarming

The affected area should be immersed in water heated 40-42oC (104-107.6oF). Ideally circulating water should be used so that temperature can be maintained. Gentle active motion of the extremity during rewarming may be helpful. Dry heat is not recommended as it is difficult to regulate.³

The rewarming process may be painful, and opioids are often required for pain control during rewarming.¹ Thawing is usually complete when the tissue is red or purple and soft to the touch, typically after 15 to 30 minutes.³

Edema may start to appear within 3-5 hours after rewarming and blisters may appear within 4-24 hours.²

Thrombolysis

Frostbite is associated with vascular thrombosis of the affected tissue, therefore patients who present within 24 hours of injury and are at high risk for life altering amputation, such as amputation of multiple limbs, may benefit from administration of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) plus heparin³

Prostacyclin

Patients presenting within 48 hours of initial insult may benefit from treatment with prostacyclin with or without tPA.3 Iloprost has been shown to be successful in some studies, however the intravenous formulation is not available in the United States.

Wound Care

Following water bath, keep wounds open and allow them to dry before applying a bulky dressing. A nonadherent gauze should be applied followed by sterile fluff dressing. Sterile cotton should be placed between digits.³

It is difficult to determine tissue viability after significant hypothermia. Debridement of non-viable tissue is best delayed for several days to weeks to preserve as much tissue as possible.¹ However, large blisters that cross joints should be drained and debrided. Large hemorrhagic bullae that cross joints should be drained by aspiration, but not debrided. Minor bullae should be left intact.³

Topical aloe should be applied with dressing changes and patient should be given oral ibuprofen or aspirin which may limit inflammation.³

Infection Prophylaxis

Tetanus prophylaxis is recommended as frostbite is a tetanus prone wound. Daily or twice daily whirlpool treatments are used to help reduce bacterial colonization of the injured tissue. Topical antibiotics can cause maceration should be avoided.³ Prophylactic antibiotics are controversial and have not been shown to reduce risk of amputation. Patients with prolonged evacuation time and sings of infection should be treated with antibiotics.⁵

Complications

The complications of frostbite are primarily due to peripheral nerve vascular injury and associated abnormalities of sympathetic tone and include:³

Vasospasm, especially with reexposure to cold

Gangrene and infection of the affected area

Autoamputation

Throbbing pain, may last weeks or months

Parasthesias, may last for months

Hyperhidrosis

Hypersensitivity to the cold

Scarring

Tissue atrophy

Arthritis

Cold exposure should be avoided for 6 months after minor injuries and at least 12 months after significant injury.

Back To Our Case

Having accurately identified frostbite, you immerse the patient’s feet in circulating heated water and make sure that is pain is adequately controlled. The patient is monitored closely during rewarming and does not develop any hemorrhagic blisters. You feel confident that this is a case of second-degree frost bite.

Following rewarming, a bulky dressing is applied, and family is instructed to apply aloe with dressing changes. Patient is started on ibuprofen to limit inflammation. He is discharged with close follow up and is disappointed to learn that he will need to avoid further cold exposure (including his favorite pastime of sledding) for 6 months.

Bottom Line

Frostbite occurs when tissues are exposed to temperatures below their freezing point, typically below 0oC (32oF), and occurs most commonly in the earlobes, noses, hands, and feet. Injury can range from superficial damage to the epidermis to damage extending to the muscle and bone. Initial examination may underestimate the extent of damage. Rewarming is key, however should be delayed if there is a risk of refreezing. In the hospital setting, the affected area should be immersed in water heated 40-42oC (104-107.6oF). Opioids are recommended for pain control during rewarming. Topical aloe and either ibuprofen or aspirin are key components of wound care after rewarming.

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References:

Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Just the Facts, 2e.: McGraw Hill; 2013.

Basit H, Wallen TJ, Dudley C. Frostbite. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Zafren K, Mechem C. Frostbite: Emergency care and prevention. 2021; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/frostbite-emergency-care-and-prevention.

Grieve AW, Davis P, Dhillon S, Richards P, Hillebrandt D, Imray CH. A clinical review of the management of frostbite. J R Army Med Corps. 2011;157(1):73-78.

Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35(2):281-299.