Dog and Cat Bites

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

Case

A 5-year-old male presents after being bit on the arm by the family dog. He was playing with the dog and when he went to take the toy away from the dog and the dog bit him on the left arm just prior to arrival. Patient has a 2 cm wound to his left arm. Bleeding is controlled. Family is anxious about whether he will need stitches.

Dog Bites

Dog bites account for approximately 90% of animal bites. Most dog bites occur in children, with the highest incidence in boys between five and nine years old.1

Fatalities are rare, but disproportionately affect children under 10 years old. In young children dog bites usually involve the head and neck, while in older children and adults dog bites usually involve the extremities. Injuries can range from minor wounds such as scratches and abrasions to major wounds such as open lacerations and crush injures. The jaws of large dogs can exert enough force to damage underlying structures. A dog bite to the head of a child may penetrate the skull, leading to depressed skull fracture, local infection, or brain abscess.2

Cat Bites

Cat bites account for approximately 10% of animal bites and occur most often in adult women.2 Cat bites typically occur on the extremities. While at first glance the injury may seem less severe than those caused by dogs, they tend to be deep puncture wounds that are difficult to cleanse and are more likely to develop deep infections.1

Imaging

Imaging is not needed for most superficial bites. Radiographs should be obtained for deep wounds, especially those near joints to evaluate for foreign bodies (embedded teeth), fracture, or joint disruption. Computer tomography (CT) of the head should be obtained in children under three years old with a dog bite to the scalp to evaluate for penetrating injury of the skull. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be obtained if there is concern for deep infection such as osteomyelitis or pyomyositis.2

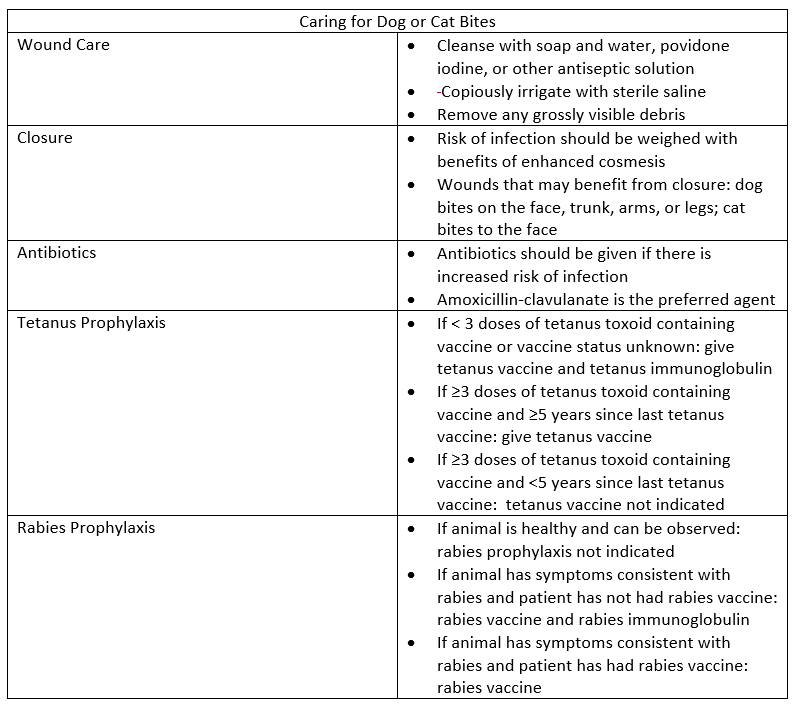

Wound Care

Wound management is the most important factor in preventing infection.

Bleeding should be controlled by applying direct pressure. Wounds should be cleansed with soap and water, povidone iodine, or other antiseptic solution. The wound should be copiously irrigated with sterile saline and removal of any grossly visible debris.3

When deciding on closure, the benefit of enhanced cosmesis should be weighed with the risk of infection.2

Wounds that should be left open to heal by secondary intention include:

Crush injuries

Puncture wounds

Cat bite wounds (unless on the face)

Wounds involving the hands and feet

Wounds greater than 12 hours old (greater than 24 hours old if involving the face)

Immunocompromised host status

Patients with venous stasis

Wounds that benefit from primary closure include:

Simple lacerations due to dog bites on the face, trunk, arms, or legs

Cat bites to the face

Bite wounds that are closed should have no signs of infection. Subcutaneous sutures should be avoided or used sparingly due to increased risk of infection. Tissue adhesive such as Dermabond should not be used.2

Surgical consultation should be obtained in the setting of complex facial laceration, deep wounds that penetrate bone or joints, and wounds associated with neurovascular compromise.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be given when there is an increased risk of infection2:

Wounds undergoing primary closure or surgical repair

Wounds on the hand, face, or genitals

Wounds close to a bone or joint

Wounds in areas of venous or lymphatic compromise

Immunocompromised hosts

Deep puncture wounds

Wounds with associated crush injury

Antibiotics should cover Pasteurella multocida (Isolated from 50% of dog bite wounds and 75% of cat bite wounds), anaerobic bacteria, and skin flora including staphylococcus and streptococcus.1,4

The preferred agent is amoxicillin-clavulanate: adults 875/125 mg twice daily, children 25 mg/kg/dose (amoxicillin component) twice daily.

Alternative regimens include an antibiotic with activity against Pasteurella multocida (doxycycline, TMP-SMX, penicillin V, cefuroxime, ciprofloxacin, or levofloxacin) plus an agent with anaerobic activity (metronidazole or clindamycin) or monotherapy with a fluroquinolone.

Treatment with parenteral antibiotics may be warranted in the case of:

Signs of systemic toxicity: fever, hypotension, sustained tachycardia

Deep infection: septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, tenosynovitis, bacteremia, necrotizing soft tissue infection

Bite located near an indwelling devise such as a prosthetic joint

Rapid progression of erythema

Inability to tolerate oral therapy

Ampicillin-sulbactam is the drug of choice when parental therapy is indicated, with piperacillin-tazobactam as an alternative. In cases of severe infection, consider adding vancomycin to cover for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.1

Patients should be reassessed in 24-48 hours to monitor for signs and symptoms of infection. Patients being treated preemptively should receive 5 days of antibiotics. Those with more severe infections should be treated for 10-14 days, and should be extended to 4 to 6 weeks in the case of bone or joint infection.1

Tetanus Prophylaxis

Animal bites are considered tetanus-prone wounds; therefore, tetanus immunization status should be determined in all patients who have suffered from an animal bite.

Patients with less than 3 previous doses of a tetanus vaccine or unknown vaccination status should be given both tetanus immune globulin and tetanus vaccine. If the patient has had three or more doses of a tetanus vaccine should be given a tetanus vaccine if it has been 5 or more years since their last vaccine.1

Rabies Prophylaxis

Animals that are healthy and able to be quarantined should be monitored for 10 days. If they are healthy after 10 days, post exposure prophylaxis for rabies is not indicated.

Animals that are not able to be monitored and have symptoms consistent with rabies should be tested if possible. Post exposure prophylaxis should be started.1

If not previously vaccinated:

Rabies immune globulin, 20 units/kg; as much of the full does as feasible should be infiltrated around the wounds and the remaining given intramuscularly

Rabies vaccine should be given at days 0, 3, 7, and 14

If previously vaccinated, rabies immune globulin is not indicated. Rabies vaccine should be given on days 0 and 3.

Back to Our Case

After further discussion with the family, you find out the dog is a German Shepard. Given that is a large breed of dog you obtain an x-ray of the arm and are able to rule out fracture. Given the size and location you feel that the wound will benefit from loose approximation. You be sure to irrigate it copiously prior to repair and give good anticipatory guidance on signs and symptoms of infection. Both the patient and dog are up to date on vaccinations. The dog is healthy and able to be observed. Therefore, tetanus and rabies prophylaxis are not indicated. You discharge the patient home with 5 days of prophylactic amoxicillin-clavulanate and instructions to follow up with his primary care physician in 1-2 days for a wound check.

Bottom Line

Good wound care is key when caring for a patient with a dog or cat bite as infection is common. All wounds should be cleaned and copiously irrigated. When deciding on repair, risk of infection should be weighted with benefit of cosmesis. Skin glue should not be used for repair. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered when there is increased risk of infection. The preferred agent is amoxicillin-clavulanate. Patients should also be evaluated to determine if tetanus or rabies prophylaxis is needed.

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References

Bula-Rudas FJ, Olcott JL. Human and Animal Bites. Pediatr Rev. 2018;39(10):490-500.

Baddour LM, Harper M. Animal bites (dogs, cats, and other animals): Evaluation and management. 2021; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/animal-bites-dogs-cats-and-other-animals-evaluation-and-management.

Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, Tang A, Gries L, Joseph B. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):641-648.

Esposito S, Picciolli I, Semino M, Principi N. Dog and cat bite-associated infections in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(8):971-976.