Adverse Childhood Experiences

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto

We frequently think of children as having the ability to bounce back from stressful situations. However, evidence shows that prolonged stress and trauma can interrupt healthy development and put children at risk for lifelong health complications.

What Are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events in a child’s life that, while common, may be unrecognized. While everyone experiences stress at some point in their life, chronic stress over a prolonged period can damage both the body and the brain. Because early childhood is critical for development, the effect of toxic stress has an even more profound effect on children.

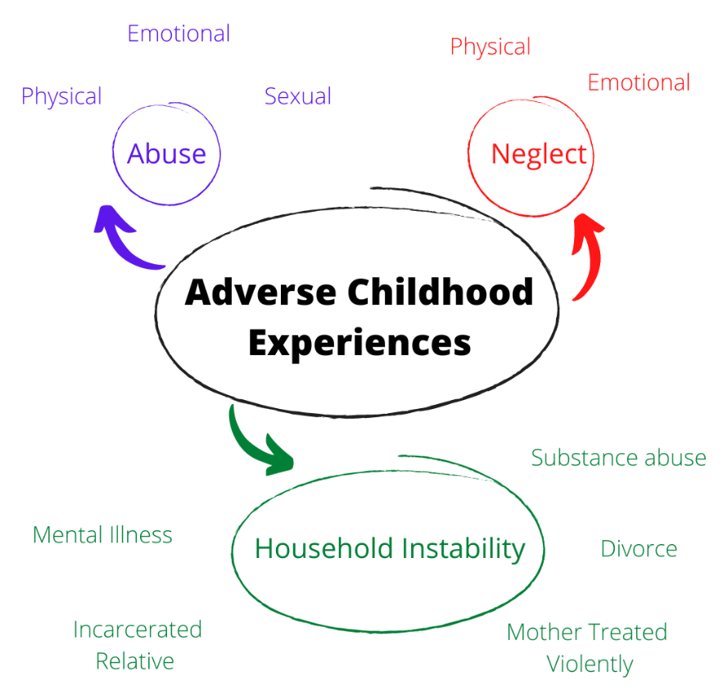

The term ACEs was coined in 1998 with the Adverse Childhood Experiences study, and are grouped into three domains: abuse (emotional, physical, sexual), neglect (emotional, physical), and household dysfunction (domestic violence, substance abuse, mental illness, criminal activity).¹ Subsequently other ACEs including extreme economic adversity, traumatic loss of a loved one, sudden and frequent relocations, serious accidents or illness, bullying, school violence, and community violence have been described.² Studies have shown that over time, exposure to multiple ACEs can affect the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems as well has having lasting effects on attention, behavior, decision making, and response to stress.

ACEs have been linked to multiple poor health outcomes. Children with multiple ACEs may have language delays, behavior problems, injuries, and obesity. Adults who experienced ACEs are at higher risk for suicide, alcoholism, illicit drug use, depression, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, cancer, and reduced life expectancy.¹,³

Nearly 60% of the adult population has experienced one or more ACE. Because ACEs represent a cluster of interpersonal risk factors, exposure to one ACE increases the likelihood of exposure to another ACE, and those in lower socioeconomic regions are more likely to experience four or more ACE.³ Given their prevalence and association with poor health outcomes, it is important to screen for and work to prevent the potentially negative impact of ACEs.

Screening for ACEs

Screening in the pediatric medical setting provides an opportunity for early detection, intervention, and treatment of children at risk for ACEs.4 As providers, we may think about screening patients who come in with complaints that may be related to ACEs, such as a child with frequent stomachaches or behavioral concerns. However, given the substantial variability in how toxic stress presents, it is also important to screen asymptomatic patients.³,⁴

In addition, it may be beneficial to screen parents for their own childhood ACEs in addition to screening children, as studies have shown that children of parents with their own childhood trauma have the greatest impact from intervention.³

There is no standardized method for when or how to screen for ACEs. Integrating screening into clinical workflow alongside other screening tools may be of benefit.

There are several screening tools including:

The Original ACE Questionnaire: https://www.theannainstitute.org/Finding%20Your%20ACE%20Score.pdf

The Center for Youth Wellness ACE Questionnaire: https://centerforyouthwellness.org/aceq-pdf/

Pediatric ACE Screening and Related Life-Events Screener (PEARLS) and ACE Questionnaire for Adults: https://www.acesaware.org/learn-about-screening/screening-tools/screening-tools-additional-languages/

Addressing ACEs

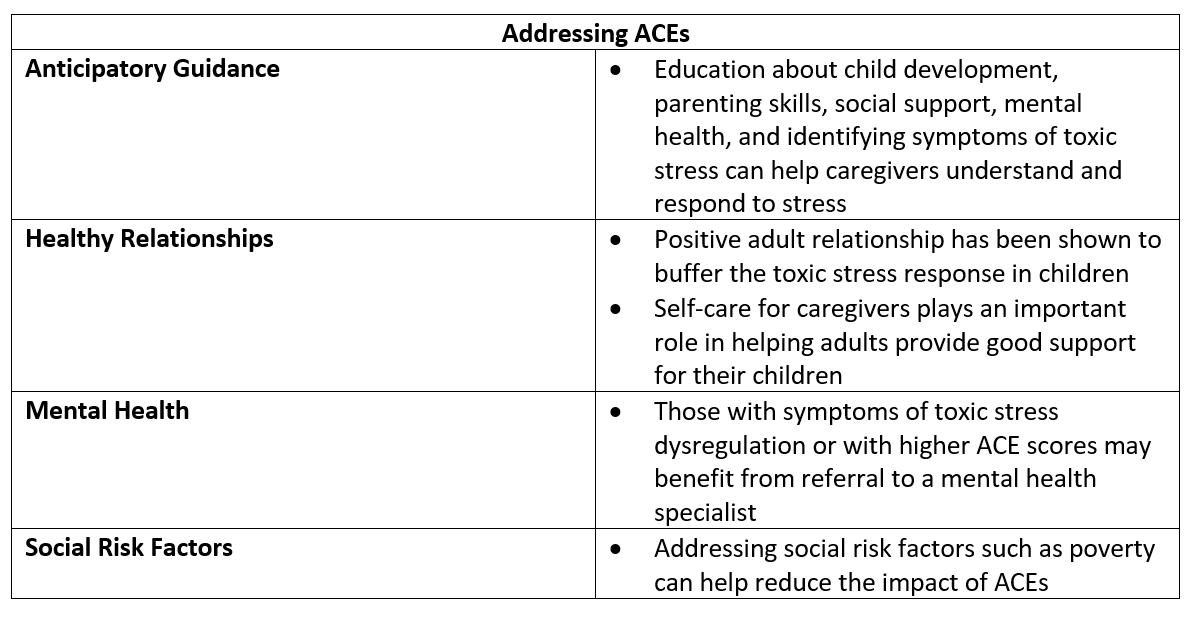

Anticipatory Guidance

Providing anticipatory guidance can help caregivers understand ACEs and toxic stress. It should be attuned to the situations that may be causing stress and give information to be able to identify potential symptoms of toxic stress (such as difficulty focusing, poor sleep, poor control of asthma, anxiety).⁴ Anticipatory guidance can also increase a caregiver’s understanding of their role as a buffer to their child’s stress and can help provide tools to help build resilience.⁴ When giving anticipatory guidance, it is important to reinforce that approximately two-thirds of adults have experienced at least one ACE and that parents likely have experienced their own ACEs.

When giving anticipatory guidance, pediatric providers can incorporate education about child development, parenting skills, and social support for parents into their visits.³ Adult providers can address mental health and substance use in their patients.³

Healthy Relationships

Having a positive adult relationship has been shown to buffer the toxic stress response in children, even in the context of significant adversity. Conversely, lack of social support has been shown to have a greater risk factor in mortality for adults.⁴ It is important to note that parental ACEs and mental health may make it difficult to model good stress response and self-regulation tools. Therefore, supporting a caregiver’s physical and mental health can improve their child’s health as well. Self-care for caregivers incudes managing their own stress through health relationships, nutritious meals, adequate sleep, physical activity, and tending to their own mental health.⁴

Mental Health

Those with symptoms of toxic stress dysregulation or with higher ACE scores may benefit from referral to a mental health specialist. Studies have shown that home visits by mental health professionals and community nurses in conjunction with parenting education and connection to community resources have improved health outcomes.³ In addition, support programs and psychological intervention have been shown to improve health outcomes such as lowering blood pressure and improving diabetes management.⁴

Social Risk Factors

Addressing social risk factors, such as the impacts of poverty, is one strategy to help reduce the impact of ACEs. Programs such as Reach Out and Read (https://reachoutandread.org/) that provides books to children and Medical-Legal partnerships have been shown to improve outcomes for low-income families.³ When implementing these programs, it is important to remember that ACEs are prevalent across all socioeconomic strata, so reducing the public health impact of ACEs requires interventions that can be applied to all socioeconomic strata.³

Final Thoughts

ACEs are potentially traumatic events in a child’s life that, while common, may be unrecognized. There is no standardized method for when or how to screen for ACEs, however incorporating screening with other screening tools has the potential to benefit both children and adults. Providers can help combat the adverse effects of ACEs by incorporating anticipatory guidance into their visits, including discussions about mental health, parenting skills, and social supports. Promoting healthy relationships and referral to mental health providers for both adults and children can improve health outcomes.

For more information, including suggested counseling and screening tips:

Center for Youth and Wellness https://centerforyouthwellness.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CYW-ACE-Q-USer-Guide-copy.pdf

Healthy Children https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/emotional-wellness/Building-Resilience/Pages/ACEs-Adverse-Childhood-Experiences.aspx

Center for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html

Elizabeth Lehto, D.O.

University of Louisville | UL · Department of Pediatrics | Doctor of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Dr. Elizabeth Lehto is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Attending at Norton Womens and Children’s Hospital. Dr. Lehto attended Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Louisville.

References

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258.

Oral R, Ramirez M, Coohey C, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: the future of health care. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(1-2):227-233.

Marie-Mitchell A, Kostolansky R. A Systematic Review of Trials to Improve Child Outcomes Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):756-764.

Gilgoff R, Singh L, Koita K, Gentile B, Marques SS. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Outcomes, and Interventions. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2020;67(2):259-273.